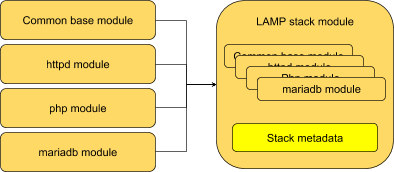

We can then combine modules into stacks.

A stack should represent something distinct that the user wants. It may be a traditional developer stack (LAMP, ruby-on-rails, etc.); or it may be an application (but extended to include all the dependencies that that application needs to run); or it could be the set of modules needed to deliver something like Atomic Host or Cockpit.

The stack represents this full set of software. It doesn’t presume how we distribute it, we’re still just talking about the set of modules making up the stack.

A stack is still just a module here. It’s just a way of referring to the module plus all its implied dependencies as a single unit, to distinguish that from the individual modules within the stack; the stack content and metadata may have exactly the same format as module metadata (the metadata is the same colour here for a reason!) But it’s still important to make the distinction between a single module, and a module plus all the external dependencies it relies on.

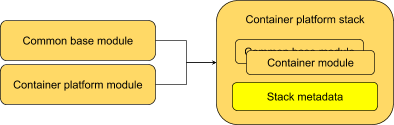

Importantly, we can take two modules with different lifecycles and combine them in a single stack. The definition of the stack gives us the way to plan and track the relationship or dependency between the modules.